critics

Alicia Viteri

Author: Monica E. Kupfer

ArtNexus No. 52 - Apr 2004

Alicia Viteri’s entire oeuvre is based on the observation of human beings, a fact that has never been clearer than in her innovative recent production of graphic works. From an autobiographical perspective, Viteri’s “Memoria digital” (Digital Memory) exhibition offers a survey of different stages in the artist’s life, highly colorful visions that include people from her inner circle and constant images of herself. In a psychedelic world of waves, swirls, and agitated strokes, Viteri’s figures appear surrounded by gardens, butterflies, trees, mountains, and open skies. These works, however, do not deny a certain element of darkness in her life, represented by shadows of the past and somber situations of the present.

Characterized by a velvet-like texture, Viteri’s colors in this new series are intense, even provocative, and at the same time joyful and spontaneous. Her strokes are impressively fluid, almost liquid, and leave no evidence of their mechanical imprinting: there are no distinguishable dots or grids to interrupt the artist’s reverie-like visions of a life. Technically, they represent a radical departure in Viteri’s work. Known as a painter and printmaker, she now embraces an exploration of digital media as a new vehicle for self-expression. A statement at the entrance to the gallery and also in the show’s catalog informs us that these pieces were created on a Macintosh computer with the Zbrush and Photoshop programs, and later printed on paper “in reproductions that are certified, approved, numbered, and signed by the artist.” The method and durability of the technique known as “giclée” —in this case, employed as a method of printmaking rather than of reproduction—are also clarified, defining it as a sophisticated version of inkjet printing in which each square inch of paper is sprayed with up to two million drops of pigmented ink, thereby achieving a highly uniform surface. The artist is exploring areas still unknown to most, using a new technique that offers the benefit of printing her series in parts while maintaining the professional ethics implied in the notion of limited editions and the hand of the artist as the image’s creator.

Alicia Viteri is known in Panama, where she has lived since 1972, for a career that has included intense periods of graphic production and easel painting. Her etchings from the 1970s were characterized by detailed images of anthropomorphic insects, creatures in metamorphosis that displayed human peculiarities. In those years, Viteri was not only devoted to her own graphic work but also played a valuable role in teaching printmaking in Panama, where she took active part in workshops at the Universidad Nacional and the Instituto Panameño de Arte. Later, her etchings began to incorporate human figures, particularly “mummies” and women, characters that over time would also show up in her canvas works. In paintings that offered a critical assessment of the social and political situation, Viteri created a theater of her own in which military figures, kings, gringos, high society ladies, and businessmen interacted representing a world of two-faced characters, farces, and superstitions. She marked a turning point in Panamanian art when she presented the installation Espacios pictóricos, which combined two friezes, one of “Carnivals” and the other of “Funerals,” with life-sized figures and the noise of a crowd in audio; an innovative piece that incorporated the viewer into its environment.

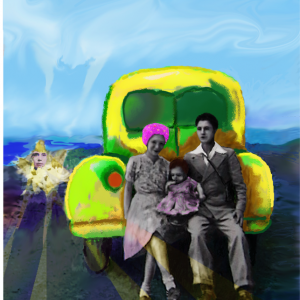

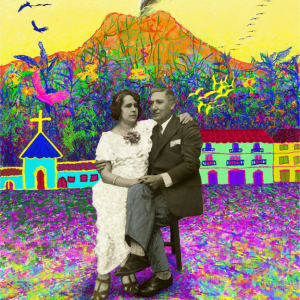

In the 1990s, Alicia Viteri again changed paths, becoming primarily interested in painting coastal landscapes, trees, and forests, pictorial exercises in which she explored color and light in the natural world, but which lacked that sharp vision of humanity that has distinguished her as an artist. In her new digital works, landscape reappears as a function of the visual context, but also as an emotional background over which Viteri develops her personal drama in a new existential interpretation. Viteri employs old restored photographs in compositions where the brushwork is replaced by the restless strokes of an electronic pencil in a wide variety of tones and thicknesses.

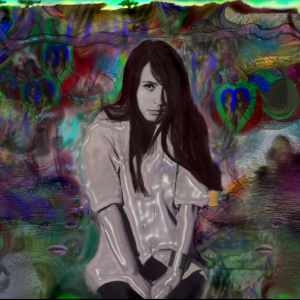

The series reflect experiences from her life such as her mother’s love, a childhood of gardens and hearts, school years with nuns and graduation gowns, a long-haired adolescence and, as if in a whirlwind that leads to the present, the encounter with her life-long partner. Viteri’s parents and older siblings make an appearance, as does her husband and the mountainous, nostalgic landscape of her native Pasto (Colombia). The path reaches the present, a period in which the artist has faced significant challenges to her health, which she illustrates without complaints and even with a sense of humor, showing herself bald but strong in the swirling waters of Caracoleando, or impotent but optimistic in the face of her illness in Como el huevo.

Beyond the catharsis that such a survey of her life could mean for the artist, these pieces reveal a sense of aesthetics that ties a certain nostalgia for black and white imagery and the styles of the 1970s to those of the computerized present, combining digital elements with graphic and pictorial ones. Viteri paints on her computer as she would do on a canvas, showing care for composition, content, and technique. Observing these prints, we are aware of the movements of her hand, particularly in her trees, plants, and other natural elements. At the same time, she takes advantage of the versatility offered by this new language in order to incorporate into her design all kinds of pre-existing graphic elements, such as butterflies, flowers, and stars, inserting repetitive motifs when her compositions require them. By manipulating, cutting, painting, and repeating photographic images, Viteri achieves a marriage between these and their surrounding environment. She handles color with admirable freedom, benefiting from the possibilities offered by a digital world where forms exist within a mutable environment, without the permanence of an engraved line on a metal plate or of ink absorbed by a piece of paper.

Among her early self-portraits, we find in Guagua the image of a girl with an innocent expression but a serious gaze. Against a mountainous landscape, a whirlwind on her head produces a myriad of colorful butterflies, like hopes for an as-yet-unknown future. In Mamá corazón, Alicia appears as a child with a huge yellow bow on her head, over which the artist painted a large red heart crowned by multicolored stars, all surrounded by the faces of ghost-like memories. There is great tenderness in Mamá con estrellas, a drawing of a young girl who rests her head on her mother’s lap, while the mother with a hand on her lips gazes into the distance, as if intuiting a dark cloud in the starry sky. Alicia’s life culminates in recent self-portraits where she appears hairless, including funny scenes such as that in Cucú, where we see her conversing with a farcical couple reminiscent of her earlier works, the man dressed as a clown and the woman wearing a low-cut dress and multi-colored jewelry. Alicia appears in a humorous pose, with tinted glasses and a white suit, holding a yellow portfolio. The scene is surrounded by an exotic garden, with a mountain range in the deep background.

“Memoria digital” is the product of many years of artistic exploration, of a mind that dares to innovate, and of a life with peaks and valleys that Alicia Viteri has been able to process into works of art charged with nostalgia and good humor.